New Netherland was a colony founded by the Dutch on the east coast of North America in the seventeenth century, which vanished when the English wrested control of it in 1664, turning its capital, New Amsterdam, into New York City. It extended from Albany, New York, in the north to Delaware in the south. It encompassed parts of what are now the states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Connecticut and Delaware.

New Netherland got underway at about the same time the Pilgrims were settling Cape Cod and the Jamestown colony was establishing itself in Virginia, but you wouldn't know that from most history books. To visit New Netherland is to see familiar places in new ways. It is to see Manhattan not as the steel-and-concrete center of the financial world, but a forested island with a tiny, rough-and-ready European settlement clinging to its southern tip. It is to imagine what is now the northeastern United States as a virgin wilderness, inhabited by native Americans and small groups of European settlers, who navigated not by roads or even forest paths but by the watery highways of the region: the Hudson, Delaware, and Connecticut Rivers. In New Netherland you will discover familiar-sounding places: Lang Eylant (Long Island), Breuckelen (Brooklyn), Haarlem, Staten Eylant (Staten Island) (named after the "Staten Generaal" or States General, the governing body in the seventeenth-century Netherlands)—all testaments to the legacy of New Netherland and its contributions to American history and culture.

But place names only scratch the surface of New Netherland's legacy. From Santa Claus to log cabins, pancakes to cole slaw, multiculturalism to upward mobility, New Netherland influenced American culture in surprising ways.

Albany Region Overview

|

A view of North Pearl Street near State Street in Albany, as it appeared around the turn of the 19th century, |

The capital city of New York has an unusually patchwork history. Needless to say, the area was under Dutch control before it fell into English hands, but even in the Dutch period there were three distinct entities that vied with one another over territory and rights.

It all started, of course, with beavers. “The people of the Countrie came flocking aboard…and many brought us Bevers skinnes, and Otters skinnes,” wrote Robert Juet, an officer aboard Henry Hudson’s Half Moon, as he gave his account of the first Dutch-financed exploration up the river that now bears Hudson’s name. The ship was then at a spot on the western shore of the river near where another, east-west system, the Mohawk River Valley, joined it. Thus began the Dutch awareness that this confluence marked a vital spot for what would be the primary activity of New Netherland: trading with the Indians for furs. Beginning in a remarkably short time following Hudson’s voyage, Dutch traders were on the scene. The town that sprang up—Beverwijck, later Albany—grew to become the second city in New Netherland, after New Amsterdam, and eventually the capital of New York State.

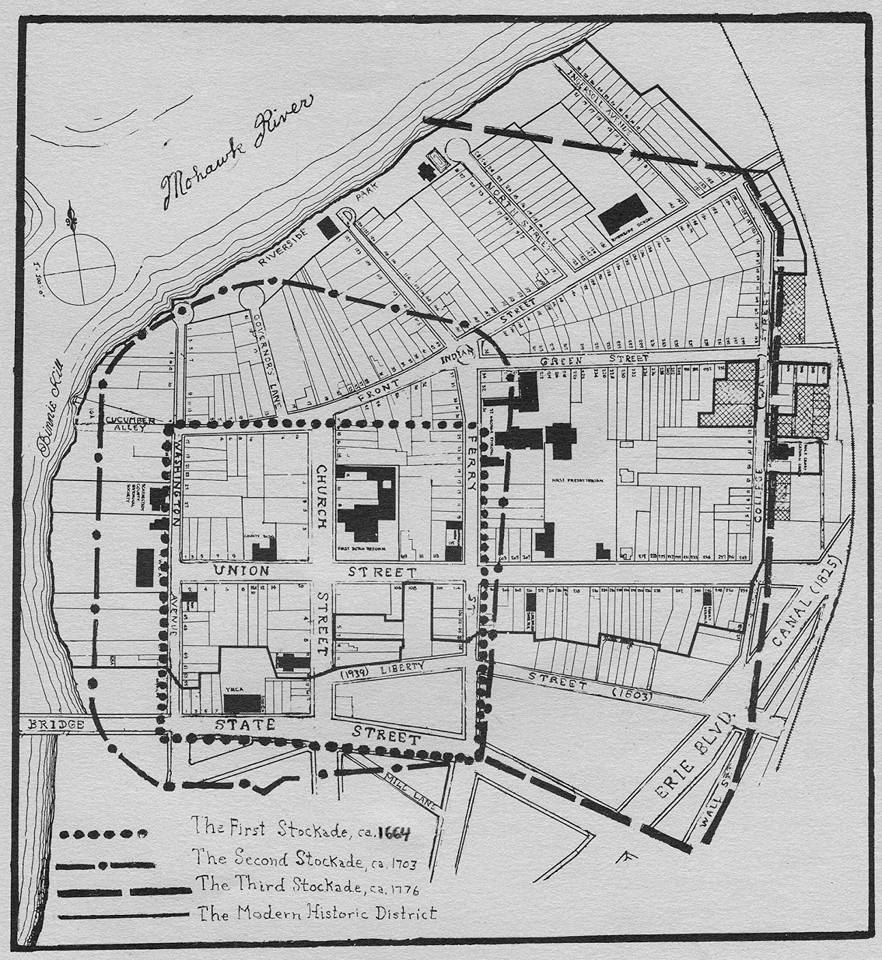

Mohawk River

The Hudson River is known all over the world as the major waterway that runs by Manhattan Island and north into New York State. The Hudson made New York City and New York State what they are today. But Manhattan would never have become the center of power it is without another waterway.

When the Dutch established their settlements in New Netherland, one of the first sites they chose was near the spot where the Mohawk River empties into the Hudson 150 miles to the north of what became New York City. The Mohawk, which extended nearly all the way to the Great Lakes, was a main water highway through the lands of the five nations of the Iroquois Confederacy. The Mohawk Indians in particular traveled down it in their canoes, bringing furs to trade with the Dutch.

Crossing from the Hudson to the Mohawk was difficult and dangerous. The Cohoes Falls ,which tumble 70 feet as the Mohawk nears the end of its course, as well as many rapids and treacherous bends, kept the Dutch mostly content to let the Indians come to them. In the winter of 1634-35, however, a hearty young man named Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert, who had been hired as the surgeon of Fort Orange, led a small party of adventurers on a mission into Mohawk country. Their arduous journey, on foot through an icy wilderness, resulted in one of the earliest visits by Europeans to Mohawk villages. In a journal he made during his trip, Van den Bogaert also made a list of Mohawk vocabulary, the first of its kind.

One of the first European settlements along the Mohawk began when Arent Van Curler, who worked for the patroon Kiliaen van Rensselaer at his vast colony of Rensselaerswijck (now Albany), led a party of disgruntled tenant farmers 20 miles upriver from the Falls and began a community that would grow into the city of Schenectady. (The town's name comes from a Mohawk word meaning "near the pines.")

The major breakthrough, both for the Mohawk River communities and for New York City, came in the early nineteenth century, when the Erie Canal was constructed, connecting Albany with Buffalo on the shores of Lake Erie, more than 350 miles away. The great interior of the continent was open to settlers, and New York City became the nation's main hub.

~~~~~~~~~~~

[The following information is from pp. 9-27 of Schermerhorn Genealogy and Family Chronicles by Richard Schermerhorn, Jr. (New York: Tobias A. Wright, Publisher, 1914).]

DUTCH EMIGRATION

The incentive of the Dutch for emigration was of a far different character from that of most of the other nationalities, and their settlements were more independent. They came of their own free will and choice, with a spirit of enterprise and adventure predominant, and they brought with them the sturdy qualifications of their race — qualifications which had safely borne them through the particularly severe struggles and trials of earlier years. They were a broad minded people in every sense of the word and enterprising to the extreme. They were industrious, honest, frugal and particularly respectable. The majority were of small means at the time of their arrival, but on the other hand, many were possessors of considerable property and even brought servants with them. Others were youths still in their teens. They were, throughout, of a superior class of people in matters of enterprise, intellect, principle and birth, and this explains the fact that their influence, predominant in the beginning, lasted so long after the rule of the land was taken from them, and even in spite of their assimilation with later emigrants of other nationalities far exceeding them in numbers. The majority of the original Dutch settlers were farmers and mechanics, but many were well educated. Public schools had existed in Holland since the middle ages, and in this respect Holland took the lead among European countries. One of the first provisions, when the West India Company was formed, was for Ministers and Schoolmasters for New Netherland. To maintain a learned clergy was regarded by the Dutch as one of the chief functions of general education. Thus with the physical vigor, inherited and maintained through their almost continual strife against the contending elements and obstacles in Holland, and a mental training resulting from strictly applied courses of education, it is no wonder that the Dutchmen came to America well endowed to struggle successfully with all of the problems they must necessarily encounter in the task of developing a new country.

To go back to the early events leading to the settlement of New York, the story begins with Hendrick Hudson, who sailed for America in 1609, his expedition being fitted out by a company of Amsterdam merchants. Though he did not discover the north-east passage to India, what he did discover proved of far greater significance. In 1612 Adrian Block and Hendrick Christiansen sailed from Holland to America, Christiansen making at least ten voyages between 1612 and 1621. It is recorded that in 1613, Sir John Argall, with a semi-piratical squadron under English colors, entered New York harbor, and found a few dwellings in the southern extremity of Manhattan Island, probably those erected by Block, while rebuilding his burned vessel. In 1614, a number of ships were sent out by a company of Holland merchants, and it is said that a fort was erected on the lower end of Manhattan Island, and the next year a fort and trading station was built on Castle Island, just below Albany. This latter was swept away in 1617 by a freshet and the site was abandoned, a new fort being erected on an eminence at the mouth of the Normanskill. In June, 1621, the West India Company was formed, with a sovereign power of trade and government in connection with all of the Dutch foreign possessions, the East Indies excluded. As a matter of fact, the first object of this company was war with Spain, and the population of the American lands was wholly incidental. But arrangements to form settlements in New Netherland were nevertheless soon projected.

There were many foreigners in Holland who had taken up their temporary residence there to escape religious persecution. The first actual emigrants to New Netherland consisted chiefly of these families, French Protestants or Walloons, from the Belgic Netherlands, who sailed from Amsterdam in March, 1623. Though most of the elders of this party were not of Dutch extraction, it might be said that the young people were, as they had mostly been born in Leyden, and elsewhere in Holland, had attended Dutch schools and were loyal to the country of their birth. Eighteen of these families settled at what is now Albany. Eight passengers were left at Manhattan Island, four with eight seamen were sent to New Jersey, where they formed a settlement, and the remainder became the earliest settlers of Connecticut. The settlers who had disembarked up the Hudson, soon built a fort, which they called Fort Orange, about four miles above an earlier fort called Fort Nassau. This settlement at Fort Orange, however, was practically abandoned in 1628, owing to the desire to concentrate all agricultural settlers at Manhattan. The real permanent settlement was made at Manhattan in 1625, and in 1626 a much larger body of emigrants joined the earliest arrivals. In this same year a return ship from New Amsterdam to Holland, carried a cargo Of 7246 beaver skins and more than 1000 peltries of other kinds, valued at 45,000 guilders (18,000 dollars, American money). This gives an idea of the extent of the New World commerce at this period, bearing in mind that the value of coin in those days was many times higher than an equal amount in these days.

In 1630, the West India Company decided upon a plan to increase the population of New Netherland, and offered certain privileges allowing private persons to take up stretches of land 16 miles long, facing a navigable river, or eight miles on either side of one, extending as far back in the country as might be. If such a person should, within four years, form a colony of at least 50 people over 15 years old, he would be patroon of a manor, having feudal rights. Several of these patroonships were awarded but only one was a success, this being the one founded by Kilaen Van Rensselaer, a wealthy diamond merchant of Amsterdam. This estate was known as the Manor of Rensselaerswyck and covered about 1000 square miles, including territory which is now the greater part of Albany and Rensselaer Counties, and a part of Columbia County. This colony from the beginning was prosperous, and it is said that this was the case on account of the high character of the people who settled there.

From this on, the settlement of New Netherland advanced substantially. In 1658, Esopus (now Kingston) was founded, and this became the next place of importance to Manhattan and Fort Orange (Albany). In 1662, Schenectady was laid out and settled, and in 1686, the Rhinebeck Precinct was purchased from the Indians and a settlement established. The towns of Brooklyn, Flatlands, Bushwick, Gravesend, Flatbush and New Utrecht on Long Island, were all settled before 1660 and Bergen and Hackensack, in New Jersey, were settled before 1670. In upper New York, Bethlehem, Hurley, New Paltz and Kinderhook were all settled before 1680, as were Tappan, Harlem, Fordham and Tarrytown nearer to New Amsterdam. Claverack, Catskill, Niskayuna, Coxsackie, Germantown, Schodack, Linlithgo, Loonenberg (Athens), Schachticoke, all Hudson River towns, were all settled at a very early date. Kinderhook, Esopus and Rhinebeck are mentioned as early as 1651, and Schodack in 1671, though it is doubtful if any permanent settlements of extent existed there at these dates.

The next land grant of importance following Van Rensselaer's, was the Manor of Livingston, which was purchased from the Indians in 1683 by Robert Livingston, and a patent was granted to him by Governor Dongan in 1684. This territory began about 5 miles below the City of Hudson, extending 12 miles down the river and back to the Massachusetts line. On this land a large number of Palatines, natives of Germany, near the Rhine, settled in 1710, on a tract known as the German Flatts. From this place they gradually scattered to other parts of the State and country, many of them locating in Schoharie County. These Palatine families frequently intermarried with the Dutch, the latter seeming to prefer them to the English.

New Netherlands changed from Dutch to English rule in 1664, when New Amsterdam surrendered to the Duke of York's emissary, Colonel Nicolls. On July 29, 1673, a Dutch fleet appeared in the Harbor and regained the City for Holland, but on Feb. 9, 1674, when a treaty of peace was signed between England and Holland, who had been at war for several years, New Netherland was ceded to England as one of the provisions of the treaty, though the final surrender was not completed until November 20th. It was not that Holland did not realize the value of her American possessions at this time, in giving up this territory so readily, but circumstances actually forced this move, England at this time having the balance of power. In spite of the change of dominion, the land tenures remained practically the same, and new patents were issued by the English to the respective proprietors for the lands they had held under the Dutch.

Emigration from Holland to America practically ceased in 1664, and thereafter New York changed from a distinctly Dutch town to one of a more cosmopolitan nature, with the English influence in the ascendency. But with the other Hudson River towns, the change was much more gradual, most of them retaining their Dutch characteristics until the beginning of the 19th century. Schenectady, indeed, was one of the last to part with its early distinctive features, and until as late as 1850 and even later, when the large manufacturing industries began to add to its population, it was known as "The Old Dutch Town." Albany adhered to its Holland traditions until a late day and Kingston still retains a superabundance of Dutch names among its residents, Kinderhook, Claverack, Schodack, Coxsackie, Catskill and other sleepy little villages, set apart from the main highways of state traffic and commerce, also continue to bear the decided impress of Dutch inheritance.

On account of the Patroonship of the Van Rensselaers and the extensive rights granted to the Livingstons of Livingston Manor, the upper part of New York State was largely under the control of a few individual landowners until a late date. Schenectady was settled as a free village in 1662, but after the Dongan Patent of 1684, there also a monopoly of land proprietorship existed, and the direction of affairs was almost wholly in the hands of Ryer Schermerhorn until his death in 1719, and even after this a long drawn out litigation resulting from the contest over the Schermerhorn rights, led to much complication in land titles. The Schenectady Patent embraced about 80,000 acres. The lands in Livingston Manor and Rensselaerwyck were allotted to the various settlers subject to what were practically perpetual leases, with a nominal rental in farm produce, and a forfeiture of 1/4 of the selling price when disposed of. This situation led to what was known as the Anti-Rent War of 1840, at which time the various land-owners undertook to dispute the titles of the Patroons. When this controversy was finally adjusted, the privileges of the Patroons had practically ceased.

The Vanderheydens of Troy, also became wealthy landowners in the latter part of the 18th century, when they found themselves in possession of a large territory of valuable land about 5 miles above Albany, on the east bank of the Hudson, extending back for several miles. For a time they exercised practically the same rights as the Van Rensselaers and Livingstons and were called the Patroons of Troy. But they were gradually induced to dispose of their property and their monopoly ceased.

This, in brief, is a general account of the early Dutch settlements in the various localities of New York State. The Knickerbocker names are fast disappearing as they have become anglicized, submerged and lost among those of the countless hordes of newcomers and the descendants of early settlers of other nationalities. But the distinctive qualities of the Dutch, inherited by successive generations of descendants, are still in evidence, even though only occasionally encountered. The patriotism of the Dutch has always been ardent, and though they accepted the English rule because there was no chance of deliverance, and though they fought bravely on the English side through the early Colonial Wars, because the battles were wholly in their own interests, it was during the War of the Revolution that their patriotism and spirit of independence were fully illustrated. Many historians do not give the Dutch Americans proper credit for the part they played during the Revolution. The early Muster Rolls and other Revolutionary documents of New York State strongly substantiate the statement that the Dutch acted in no mean capacity as Revolutionary soldiers and adherents to the American Cause.

The regard for family and church were strong features of our early Dutch ancestors. The home life was quite simple, and unaffected, but most cheerful and quite comfortable as opportunities for nicer living progressed. Duty to the church was considered above almost everything. A trip of twenty miles to Sunday services was not an unusual occurrence in the pioneer days, and besides the religious instruction they afforded, these functions were important even then as now, for the opportunities they granted for social intercourse. The church records of baptisms and marriages on the whole were faithfully kept and to these musty manuscripts we are indebted for the connecting of many a link of past kinship. In certain cases the very early records of some of the first churches in the colony have been lost or destroyed, thus unfortunately embarassing many searches for genealogical data. This is the case of the first records of the churches at New York, Albany, Schenectady, Schodack, and the Dutch villages of Long Island, as well as those on the Delaware; but as a whole, the early Dutch Church records are unusually complete, considering the many vicissitudes through which the communities passed.

The basis of the Dutch education was the learning of a trade and each young man was supposed to have some thorough education in at least one particular line, though he did not always pursue the vocation in which he had become accomplished. The first business of importance was naturally the fur trade and he who was not a fur-trader, was a farmer, excepting in the fewer instances, where individuals found it profitable to become a freighter, run a saw or grist mill or keep a shop for blacksmithing, shoemaking, selling merchandise, or following similar vocations catering to the requirements of the community. The blacksmith was often a person of considerable importance, as he was responsible for all the iron work of the district, from the elaborately worked numerals on the front doors to the numerous pots and kettles which graced the family hearth. Shoemaking would be conducted by many individuals both as a means of providing for their own families and for working to advantage during the winter months when farm work was at a standstill. Breweries were not infrequent in olden times, and those who maintained them were quite of the substantial class, for beer was the common beverage in those days, the Dutch looking askance at water as possibly injurious to the health. Most of the Dutch settlers were proficient in carpentry, as it was quite necessary that they should be, in order to rear their homesteads and develop their properties. When taking up a new property the first thing to do was to build a saw-mill, if practicable, on a nearby stream, and apply this as means for preparing the timber cut from the land for commercial use. While the primitive type of house was the log cabin, this was not popular among the Dutch, who preferred the house of brick. The latter would generally consist of two brick walls, gabled and crow stepped, with the long sides of hewn timber. The farmers in those days were the men of means, and working on virgin soil, they lived particularly well and with a fair amount of comfort and luxury for the times.

Slavery was in force in the early times, as far back, at least, as 1628, and continued until 1824, when all slaves in New York were emancipated. But the slaves were well taken care of, and, comparatively speaking, lived as well as their masters. Their children were baptized in the churches just the same as those of the white people, and they were brought up in good habits and with good care. Large numbers of slaves, naturally, it was not the habit to maintain. Ten to fifteen would be held by the wealthy landowners, though the Livingstons held three or four times as many. They were always allowed to be present at weddings and festivities of like character. They were greatly attached to the families they served, as a rule, and took great pride in their names, which they adopted from their masters, and sometimes, as may be imagined these were of much length. It is thus not unusual, although often incongruous, to encounter a coal black negro with a Dutch name as long and as harsh sounding as could be imagined. The author's brother met one quite by accident in an obscure locality in Brooklyn. "Yes sah, my name is Schermerhorn and I'm proud to say so. Col. Cornelius Schermerhorn of Schodack was my daddy's massa, sah. He was a great man, Col. Cornelius."

The principal holidays of the olden time were Kerstyd (Christmas), Nieuwjaarsdag (New Year's), Paaschdag (Easter), Pinxsterfeest (Whitsuntide), Kermis and others. The greatest one of these was New Year's. This was spent, as in recent years, in making calls, and every house was open and sideboards and tables were loaded with cakes and wines. The following is quoted from an address (in 1888) of Judge John Fitch, formerly of Schodack.

"The Hollanders, in those early days of the settlement of the valley of the Hudson, did not have so many enjoyments. Christmas was a day of rest, as well of some hilarity. It was the custom of the country for some one of the neighbors to make pitchers of hot rum (in the later days called spiced rum), of which the visitors partook freely. The well-to-do families in those days had pitchers that would hold three gallons, which were used to hold milk, used with mush, for the evening meal called supper. Sometimes they used cracked corn called 'samp' and milk, and cold meats and vegetables. Cabbage was used to a very great extent. New Year's was very similar, roast goose then being the universal dish, accompanied with the neighborly drink of hot rum. 'Paas' was a day celebrated by eating hard eggs and drinking egg cider. The latter was made of sugar, eggs and cider, thoroughly beaten up together. At 'Pingster,' the young people met together and gathered large quantities of a delicious fruit called 'Pingster' apples, also squawberries and wintergreen berries with the young growing wintergreens. These, with egg-nog, made an enjoyable feast. The 'pingster' apple is a succulent, soft pulpy fruit, growing on a bush similar in size and appearance to the lilac."

Here we may rest. It is impossible to include in small space, what might fill a large volume, but there are many works, which treat well of the habits and customs of our Dutch ancestors, and these may be readily consulted. Perhaps those who read this book and study the genealogy it contains, may feel increased interest in learning about the times of our Dutch forefathers. It is due to the latter, for what they have accomplished, that the history and traditions of the olden time be kept alive. If this work helps to maintain such a sentiment, one of the writer's objects will have been realized.

No comments:

Post a Comment